Chapter 4 - College and the Army

I was notified on February 16, 1943, by the Registrar that they had received my application for entry into the freshman class of the California Institute of Technology, and that my transcript had qualified me to take the entrance examinations. The exams were on March13, for English and Chemistry, and March 20, for Mathematics and Physics. They also informed me that the start date for the fall semester had been advanced from September to June. They asked to be notified of an instructor at Chico High that would be willing to supervise these exams if I lived too far from Pasadena to take them at Cal Tech. I was very naive about higher education, since no one had in my family had attended college, and had applied for admission to only Cal Tech. Many thanks to Mr. Carl J. Schreiter who had taken the time to give Bob DeMoss, Jim Hartwell, and me a special course in spherical trigonometry which we all needed for our plans. Bob and Jim wanted to join the Naval Aviator V5 program and I wanted to go to Cal Tech. Bob was killed in a training accident and Jim went on to fly dive-bombers in the Pacific.

I took the test at the appointed times and went with my father for an interview in Sacramento with a member of the Cal Tech faculty. I was notified of my acceptance at Cal Tech in May and was offered a LaVeren Noyce scholarship, a scholarship for those who were descendant of active members of the armed services during World War I. When I got the letter, I was ecstatic. My Father immediately went to the Pasadena area and bought a house in western Altadena at 464 Royce Street. In the meantime, after graduating from high school, I was working at any job I could get through the state employment office. I hoed weeks in a beet field, loaded fruit from a refrigerated warehouse into refrigerated box cars, and helped one elderly lady clean up her back yard. My favorite was loading the fruit, because I spent most of my time in refrigerated air and the outside temperatures were above 100.

The family, except for Ralph, who had been accepted to the Naval Academy the previous fall, loaded up the Oldsmobile and headed for Altadena the third week of June. I reported for school on the first of July and was assigned to A section, a group of 20 students that took all the required freshman classes together. I did quite well in all my classes except for calculus. I had a nineteen year old class instructor who couldn't understand why I, who, unlike many of my classmates who had not had calculus, was asking questions. His arrogant attitude didn't help matters. The freshman dean finally called me to his office and asked what the problem was. He pointed out that I had scored 18th in a group of 1200 who had taken the entrance exam and they had expected that I would do much better. I explained my troubles with the math instructor and he told me that he completely understood my problem and he wold correct it immediately. The next day I was transferred to another class. The new instructor was a Professor of Mathematics. He would explain a concept then announce that he knew we had the following question. After answering the question he would then turn to the class and ask if anyone had another question that they would like to ask. My math grades immediately jumped from D to A.

The first time I was to attend a full class Chemistry lecture I couldn't find the entrance to the lecture hall. The building was completely new to me and, after ten minutes, of searching I gave up. I made sure I was oriented before the next lecture and I listened intently to the lecturer, the world famous Noble price winner, Linus Pauling. I raised my hand to ask a question, and Professor Pauling looked at me intently and remarked that he didn't remember me from the first lecture and asked my name. I embarrassedly explained that I hadn't been able to find the door to the hall. All the students laughed and the Professor answered my questioned. Five years later I dropped in on Professor Pauling to get my Tau Beta Pi book autographed, and, when he saw me at the door he said, "come in Irving, what can I do for you". He then explained a double helix model he had on the table. He mentioned that he had the theory nearly complete. His son was attending the English University where two professors were working on the same problem. They often talked to the younger Pauling about what his father was doing but never told the son what they were doing. They won a Nobel price for their work on DNA.

Linus Pauling had the best memory of anyone I ever knew and was the finest teacher I ever had. During one lecture on ions he had carefully tended a beaker of water over a Bunsen burner during the whole lecture. At the end of the lecture as he dismissed us a student asked what the water was for. Pauling dipped a tea bag into the water and announced, "Tea ions, son, tea ions". He would often multiply two large numbers together on the black board and write the answer in one continuous line. He would then turn with a big smile and say, "I'll bet you would like to know how I did that". He would then explain how he had separated each of the numbers he was multiplying into a large number and a small residual and then, using the binomial theorem, had multiplied in his head the large simpler numbers, added the products of the large number and the residual of the second number and vice versa and could ignore the product of the two small residuals as not meaningful to the significant value of the answer. He had not only taught us a useful mathematical concept but had pointed out the importance of significant values in science.

I was running cross-country for Tech, but both the track and football teams from Stanford had joined the Navy V12 program. I was never near the front of the team at the finish. I told the coach I was going to quit, and he asked me not to. Even though I was near the back of the Tech team, I was finishing in front of most of the opposition runners and earning points for Tech, so I continued until I was drafted.

On October 5, 1943 I had my eighteenth birthday and registered for the draft. I tried to join the V12 program but was told my eyesight wasn't good enough. I then told my Father that I was going to join the Corps. He said "Like hell you are, I know most of the bastards running the Corps now and they'll get you killed for sure". He suggested I go into the Army and join the ASTP. Being an obedient son, that is what I did. I was called to a preliminary physical later in October and told to report for induction on December 3,1943. I obtained a leave of absence from Tech and reported for induction in Los Angeles at the appointed time. During my induction physical I was standing in front of the doctor naked. He asked me to hop up and down on a step stool several times. He then started listening to my heart with his stethoscope. Suddenly he dropped his stethoscope and grabbed me around the waist. As I stood staring at him he looked up and asked if I was used to extremely heavy labor. I told him I was a long distance runner and he explained his actions. My hopping up and down had raised my heartbeat to about 120 but when I stopped it only took about three beats to drop to its normal beat of 45. He thought I was having a heart attack. I was sworn into the Army and told to report to Ft MacArthur on Dec. 27, 1943.

On reporting to Ft MacArthur I was issued clothing, given an intelligence test, a test in code reading, asked if I'd ever driven a truck or could type, and assigned to the infantry. I was sent by a coal burning steam train to Camp Fannin, near Tyler, Texas. We arrived about the first of January 1944. During the trip one fellow kept opening all the windows on the train even though it was quite cold and the engine was pouring out a lot of smoke. He was bragging how he was going to be a paratrooper. About three months later he showed up in the training battalion with an MP, with shotgun, and we were asked if we minded if he trained with us. We said OK and so he trained with us with the ever present armed MP. I don't think he became a paratrooper.

We were taught personal hygiene, field hygiene and were given training in close order drill and marksmanship. During the marksmanship training the instructor wanted to know how I had learned so much about rifle marksmanship. I told him that when I was ten, my Father, a Marine Captain, had turned me over to a Marine Gunner Sergeant to teach me all about the 03 Springfield Rifle. He muttered that explains it and pronounced me ready for rifle range. When firing for qualifying I had a perfect score through the first day of qualifying that included 200 yards. Slow fire prone, sitting and offhand and 300 yards rapid firing prone and sitting. The next day I forgot my glasses when we went to the range and did a terrible job at 500 yards. My final qualification was just Marksman. I never told my Father because he would have been disappointed.

Shortly after we finished our rifle training we were in formation at attention and I collapsed in the snow. When I came to I was looking into the anxious faces of the company commander and my drill sergeant. They rushed me to the hospital were I was diagnosed with a case of mumps. I was taken to a ward for mumps and the nurse cautioned me to be very quiet and just lie in bed and don't move or I might end up like the fellow several beds down. His mumps had gone to his testicle and he was softly moaning the first week I was there. I hardly moved for a week. When I was well enough I was sent back to wait for the next training session to start. While waiting I cleaned latrines with a German POW. He and I got along quite well. I think he had been captured in Africa.

There was a large group of German POWs that had been captured in Africa, at Camp Fannin. They used to march to their work in groups of approximately fifty, and, whenever they saw any trainees, they would start chanting as cadence, "you'll be sorry, you'll be sorry".

I soon started training all over again. This time I did fine on the range again until the 500yrd firing. This time there was a dust storm, and I couldn't pick which target was mine. I shot a bunch of bulls' eyes for the fellow next to me. I did have one problem on 300-yard rapid fire. I was given eight bulls' eyes and one complete miss. I was protesting rather violently to the sergeant when an officer showed up to see what all the fuss was about. I told him that I couldn't have possible missed the whole target at three hundred yards. He asked where my other shots had hit and told him they were all in the center of the target. He ordered the target brought up from the pits and examined it. Right in the center of the target was a 2.5-inch hole with the entire target blown away. He examined it, smiled at me and said, "That's an impressive shot group soldier. I believe you and I'm going to allow a perfect score." I thanked him, saluted him, and he walked away with a smile on his face.

One of the trainees was a fellow in his early thirties we called Pop Drapper. He and I became buddies and I really enjoyed his company. We were waiting out in a wooded area one day for some reason I've forgotten. One of the kids, who was about twenty pounds heavier than the rest of us, wanted to box with anyone willing to try. He had a pair of gloves with him. He beat several of the fellows giving them black eyes or sore chins. I had never boxed so I didn't volunteer as a punching bag. The bigger fellow kept egging the rest of us to give him a try. Finally Pop volunteered. Pop must have twenty pounds lighter and four inches shorter then his opponent. I asked what the hell he was thinking about. Pop merely shrugged his shoulders, put on the gloves, and beat the tar out of the younger man, leaving him sprawling on the ground, with no more fight in him. I got Pop aside and asked him what happened, and he told me he had been a Golden Gloves champion in his weight class in Chicago.

During a hand to hand combat training class a young Lieutenant was talking to a group of about thirty of us about jujitsu and asked for a volunteer. We pushed a fellow who was about six foot four inches tall and weighed about 220 pounds out to the center of the circle. The Lieutenant was about five foot seven and probably weighed 140 pounds. He asked the volunteer to put one arm out from his side, horizontal to the ground. He then grabbed the arm, which looked like a good size tree limb, and chinned himself. The arm or the private didn't move. After several more attempts, the officer announced that what he was about to show us didn't necessarily work where there was a large disparity in size. We all broke out laughing and the officer smiled and continued the class with a different volunteer.

Part of or training was to crawl under some barbed wire with smoke and live machine gun fire just over our heads. There were occasional explosions set off as we crawled along. I was crawling along dragging my M1 by the sling near the muzzle as I had been taught when I came to a slight rise. I thought it was just part of the terrain contours and crawled up the slope. Just as I got to the crest of the of the slope an explosion went off that knocked me out. When I came to I was extremely groggy and was deaf. Fortunately I didn't try to get up, but lay there until I became oriented as to where I was, and what I was doing. I had put my head into an explosive pit just as it had been set off. I finally figured what way every one else was crawling and finished the course. It took me several hours to regain my hearing.

During mortar training I was classified as a first class mortar man. During one of our tests I got the second round right on the target and called for my assistant for three for affect no charge. He immediately started dropping the rounds down the tube. Two hit the target, which was about 400 yards away, but the third round didn't hit. About 30 seconds later we heard a dull thump of a mortar round exploding very far away. He looked distraught and muttered that he hadn't stripped the external charges from the last round. I had the mortar set for nearly maximum range to reach the target with only the shotgun shell, and with all the external charge the round must have traveled nearly 3000 yards. More about this later. During the early part of the mortar training we had been practicing setting up the mortar and sighting stakes on the drill grounds near the barracks. It had started to rain with a typical Texas down pour. By the time it started to rain and the time it took me to cap the mortar, about three or four seconds about two inches of rain fell into the mortar tube.

During part of our training we were supposed to practice climbing ropes hand over hand. Our Sergeant had the Corporal demonstrate. The Corporal then went up by using two ropes to go to the top. None of us every tied that. One day the whole platoon was asked to move a grand stand from one part of the training area to another about a hundred feet away. We all picked it up and moved, but, just as we were about to lower it, all the other guys dropped it and I was left holding up one end. I could feel my feet sinking into the dry ground and dropped the stand. I had a very badly strained back, but when I reported for sick call the Doctor said he didn't see any thing wrong and accused me of goldbricking. I was furious but went back to my platoon stopping to vomit every few minutes. My sergeant believed me, having seen what had happened, and took it easy on me for about a week. I wished I had taken the quacks' name so I could have looked him up after the war.

One of training exercises was to do a night compass course through a swamp. I was appointed patrol leader, and about five of us plunged into the swampy woods. We came to a stream that was too deep to wade across, so I handed my pack and rifle to one of the other guys then swam across and found a good landing spot on the far side. My rifle and pack were thrown over to me and with one of the fellows on the near side started assisting each member across. One fellow said he didn't need any help from any college kid and tried to jump across the stream. He landed in the middle of the stream and immediately went under. I let him thrash around for about 30 seconds but, when he went under, I dove in and hauled him to safety. I don't think he thanked me.

Later we came to a cliff and the Corporal had fallen off and was crawling around on his knees with a cigarette lighter looking for some of his gear. I decided to move to the right and try to find a better way down the cliff. In the process I fell into a crack running back from the cliff. Fortunately I hung on to my rifle when I fell and it bridged the top of the crack. I found myself dangling about ten feet above the bottom of the crack. The fellows in my patrol pulled me up and we started off again. Whenever we came to a blackberry thicket I would take an offset to the course and then correct back as soon as I could. When we finally popped out of the woods we came out right next to an officer. We were the first through and had missed our course after nearly a mile by only a few feet. The Lieutenant wanted to know how I'd accomplished that. I told him that my Father was a retired Marine Major, who had taught me how to use a military compass when I was 12 years old, and that when I was in the ROTC program at Hoover High in San Diego the training Sergeant had let me make all the sand table models for his class.

A buddy and I were hitch hiking to Tyler one day and no one was stopping to pick us up. I remarked that if we were in California some one would have picked us up by now. My buddy said, " Yeah, yeah, yeah, I'll bet". Just then a fellow pulled over and offered us a lift to town. After we got underway I asked where he was from. California was his answer, and I made a face at my buddy. The driver wanted to know what was going on, and I told of my remarks just before he had stopped for us. He laughed and said he was happy to give a ride and we both teased my buddy the rest of the short trip to Tyler.

During one of the training exercises we had just arrived in the area when something hit me in the left shoulder and knocked me down. I got up and felt my shoulder, which was fine, and then the small group started looking for what had hit me. We finally found a spent thirty-caliber rifle bullet. We showed it to the officer and he told us that we were about two miles behind the target area of the rifle range. That someone must have shot a round way above the target and that I had been hit by the spent round.

One night, late in the training cycle, we were having a night exercise. One of our training officers, a Captain, had been quite mean, and, during the darkest part of night, when you couldn't see your hand in front of your face, a group of men grabbed the Captain and threw into the middle of a black berry thicket. Fortunately, there weren't any copper heads or rattlesnakes in the thicket so the Captain got out with only severe scratches and a ruined uniform. I didn't have much to do with the officer, so I don't know whether this changed his ways.

On one-week end a fellow trainee wanted to go to town, but didn't have any money. I agreed to loan him a few bucks if he would pay me back next payday. He agreed and off he went. The next payday I went to the barracks adjacent to mine to get my money back. He refused to honor his agreement. I invited him outside to settle the problem. He laughed and said he was going to beat the hell out of me. I told him that was ok by me because while he was beating the hell out of me I was going to beat the hell out of him. He handed over my money. This concept works well in foreign policy also.

While we were on bivouac the last two weeks of training, I ended up carrying all the heavy equipment on marches. About a week before the end of training I felt a sharp pain in the arch of my right foot. It would get dull with use every day, but, every morning when I first stepped on it, I would get a very sharp pain that brought tears to my eyes. I continued limping around but didn't do any heavy lifting after that. One of the fellows wakened one morning with a copper head snake coil on his chest trying to keep warm. He rose with a shriek and, enshrouded in his shelter half, went running through the woods bouncing off of trees for about 50 yards. I don't know what happened to the snake. At the end of bivouac we had a truck of ice cream delivered to us, and we all celebrated. As we were hiking back to camp from bivouac, an officer in a peep stopped and asked who was having foot trouble. I volunteered that I had a very sore foot. He told me to throw my pack and rifle into the back of the peep and to pick them up at the orderly room when I got back.

After returning to barracks and getting cleaned up we had a good nights sleep. The next day we were standing around on the drill field when a young Second Lieutenant came up and said that I had run track in college. I allowed as I had run in high school and cross-country in college. He wanted to run a hundred-yard dash against me. I told him that I had a very sore foot and preferred not to race him. He kept egging me on so I agreed just to rid of him. I beat him by about four yards and he congratulated me on a fine race. That afternoon we were given our overseas physical. As the doctor came to me he asked if I was feeling all right. I told him no, that I had a very sore right foot. He wanted to know why the hell I didn't have my shoe off and told me to take it off. I did and he pressed down hard on my arch. I screamed and he said, " You dummy you've got a broken foot. Turn in your foot locker and report to the hospital". I went out to tell the Lieutenant that I had a broken foot and was supposed to report to the hospital. The look on his face was amazing. I don't think he wanted to believe he had been beaten in a foot race by someone with a broken foot. I got my footlocker up to the orderly room, and they had a peep take me to the hospital. I was there for about three weeks. The didn't put a cast on it - they just gave me a pair of crutches and told to stay of my foot.

During my stay in the hospital I met a Major, and we started chatting in the hall. I asked him what had happened to him. He told me that he had been teaching a class in map reading and was standing in front of a grand stand full of enlisted men when a stray mortar round landed next to him. It broke his leg and filled one side of his body with shrapnel. I thought oh my God that's where my stray mortar round had landed. I sympathized with him and quickly changed the subject of our conversation.

After I was well, I was put in a rehabilitation company for about three weeks. One day I was assigned to range guard duty. The guards were sleep in a tent. A strong wind came up that night and blew the tent down. I was in the tent when it started to go, and I barely made it out. The tent had a very substantial tent pole that I found across my bed when we re-erected the tent the next morning. We spent the rest of the night crowded into the ammunition shed.

I was given a pass for a two weeks leave at home. While home I went to Ken Murray's Blackouts of 1944 with Dorothy Gillett, the daughter of Admiral Gillett, an old, old friend of the family. We also went to the beach as often as my folks could afford it on their gas coupons. While at home I received orders to report to Advanced Infantry Training at Camp Howze, Texas.

The last week of August 1944 I headed off to Camp Howze. When my Father bid me farewell at the train station he got me aside from my Mother and Sister and told me that he didn't want me to try and be a hero. He pointed out that the main purpose of infantry combat was to make the enemy die for his country and not for me to die for mine. He told me he knew I would do my duty.

I stopped in El Paso and met some Air Force bombardier trainees at the local Army Navy Club, and we all had a good swim in the pool. I arrived late at the camp and had to scrounge around for some food. My gear hadn't arrived yet so when the Captain arrived next morning in a weapons carrier to take me out into the field, I told him I still didn't have any field gear. The Captain told me that he had always wanted to go to Cal Tech. He didn't want to go back to the field without me so he loaned me some of his officers' gear. The next morning we headed off into the Red River Valley along the northern border of Texas. The captain told me to hang on tightly because last week a man had been bounced out of the vehicle and severely hurt.

We finally arrived at the training area and the Captain told me to go down and report to a sergeant unloading ammunition from a trailer. I went down the slope, and the sergeant looked up part way, saw the pistol belt I was wearing and asked what I wanted him to do. I told him to finish unloading the trailer, and I went over and sat in the shade of a tree. When the sergeant was finished he looked at me and I told him the Captain wanted me to report to him. He let out a growl and headed for me with clenched fist. The Captain yelled, " Odgers up here on the double". Boy did I go up that hill in a hurry. When I reported to the Captain he said, " I can't leave you with him, he'll kill you. How about being my runner for a while until he settles down." I told him I really appreciated his offer. He then asked how good a shot I was, and I responded that I was an excellent shot. He told me that he wanted to add some realism to the next exercise and told to take a bandoleer of ammunition to the top of a nearby hill and shoot at the men when they were advancing. He suggested about three feet was close enough for the shots. Off I went to the top of the hill where I spent an hour shooting at GIs, running up the valley below me. By the end of the day the only friend I had in the company was the Captain.

One live fire exercise was to attack a pillbox at the end of a rising draw. The Lieutenant leading the attack was running along the top edge of the draw and I strongly suggested he get down in the draw with the rest of us. He declined the suggestion and a minute later a round cut one of his suspender straps holding his musette bag. He dove headlong about eight feet into the draw and stayed with the rest of us until the end of the exercise.

We were giving rifle grenade instructions and the instructor asked for a volunteer to fire a grenade from the standing position. I was pushed forward, loaded the rifle with around, and attached the grenade to the grenade launcher. I took a very wide stance, leaned forwards, aimed at the target, and holding the butt of the rifle as snuggle to my shoulder as I could, I squeezed of the trigger. I don't know whether I hit the target, because the next moment I found myself spun around my back foot, and facing directly away from the target. I was fine, and my shoulder hadn't been bruised or hurt in any way. The instructor complemented me on a good job and took the rifle from me.

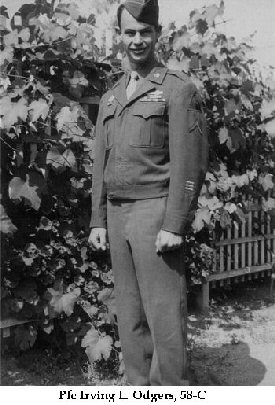

I next received orders to join the Eighth Armored Division at Camp Polk, Louisiana. The day I was to leave to join the Eighth, I learned that the night before, a bunch of privates had caught the mean sergeant and had put him into the hospital by beating him with rifle butts. During the first week of October 1944, as I was turning nineteen, I reported to Company C of the 58th Armored Infantry Battalion. I was asked what I was best at by a sergeant, and I told him I was a first class mortar man. He replied that they didn't need mortar men and assigned me to the machine gun squad of the second platoon. This was the only weapon I had failed during training, because the gun I was assigned for qualifying had a loose front sight. That's the army.

My platoon's leader was a 1st Lieutenant named Ralph Elias. He told us all to put our names on are clothes with indelible pencil. I neatly lettered my name on every thing as requested. Elias then inspected our work. He looked at my neat 1/4-inch high lettering and announced in a loud voice, " I can't read that. You're restricted to camp, and redo that so I can read it." He was the best leader I ever had in the Army, and though tough as nails, was always fair. He later warned us that he had gotten in trouble, when stationed in Iceland, because his Dad had hidden a bottle of whiskey in a package he had sent. He told us to let our folks know that they had better be very careful in how they shipped alcohol. My Mom used to send me fruitcake soaked in rum.

We ate family style in the chow hall. There were two half-track drivers in our platoon that used to clean half a platter of chops for themselves which didn't leave much for the rest of us. One weekend we went to town and, Rocco Cuteri, one of the men in the squad, got a little high. A couple of the other squad members grabbed him under each arm pit and we started back to camp, trying to keep Rocco quiet, so as not to attract the attention of the MP's. Rocco kept swinging both feet over his head trying to kick the roof of the covered sidewalks. We made it back to camp without getting into any trouble.

I trained for three weeks and qualified for the expert rifleman badge. During qualifying, a guy that weighed about twenty pounds more than I did picked me to pair up with in the fifty yard wounded man carrying exercise. I got even with him. I got the point of my shoulder in the pit of his stomach and gave him the roughest ride I could. I also went out on a field firing exercise and fired for record first and got a perfect score. Then I was told to go fire on the practice range while the other half of the company fired for record. I think the fellow at the nearest target pit had gone asleep. I hit the target and he didn't pull it down so I kept firing at the stick until finally a round just skimmed the top of the pit and hit the stick. Boy it sure came down fast then.

We had to take a twenty-five mile forced march before going overseas and I was sick when we were supposed to go. I hauled myself out of bed and went. I felt fine by the time we got back. I remember someone hauling a donkey upstairs in my barracks just before the march. I looked up from bed and saw the back end of the donkey about to sit on me.

I went to the motor pool one day and found Ray Pastewka, our half-track driver, cleaning the engine with a toothbrush. We were getting ready for a general inspection before shipping over-seas. Ray sure had the track shining clean. I was later told that the inspector was an artillery general, soon going overseas himself, and he wanted to take our artillery with him.

At the end of October 1944, we all boarded trains and headed to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. It took a number of days to get to New Jersey, and I don't remember the route we took. When we arrived, I called my Father's brother, my Uncle Chris, who wanted to come meet me. However, he was in his mid sixties and I had no idea how to direct him to a meeting so I discouraged him from coming, as much as I wanted to meet an uncle I'd never met.

|